Two Key Ingredients Incorporated Into New Generation Jails Are

Expert guest for PRI24th July 2014

- Two Key Ingredients Incorporated Into New Generation Jails Are In The World

- Two Key Ingredients Incorporated Into New Generation Jails Are Called

In the third blog of our anniversary series, Marayca Lopez i Ferrer, Senior Corrections Analyst and Planner at US firm CGL/Ricci Greene Associates, explores how forward-thinking architects are moving away from classical models of prison architecture – high perimeter razor-wire topped fences, gloomy undersized concrete cells along narrow corridors – to experiment with innovative spatial concepts which better align the physical plant of correctional facilities with the concept of humane treatment and contemporary priorities of inmate rehabilitation and successful reintegration.

Apr 01, 2007 define first,second,third generation jails? What is the difference between first second and third generation jails. 1 decade ago. Favorite Answer. The newer generation jails are not just lines of cells anymore. 'Inmate housing is based on a pod or module concept. This means that housing is broken into groups ranging from eight to forty. Oct 22, 2013 Deprivation of heterosexual relationships: physical needs/desire. Homosexual acts either a continuation from behavior or identity prior to prison OR rare acts based on intolerable pressure, power struggles. Need to define masculinity. Hypermasculinized environment. Boundaries in gender identity aren't as clear, because no females to compare to. NEW GENERATION JAILS. By William ``Ray' Nelson Chief, Jails Division National Institute of Corrections Boulder, Colorado Despite lofty claims of advanced practices and standards compliance, there is serious doubt whether most of our nearly 500 new jails will resolve fundamental custody problems that have traditionally plagued American jails. Apr 01, 2007 The newer generation jails are not just lines of cells anymore. 'Inmate housing is based on a pod or module concept. This means that housing is broken into groups ranging from eight to forty-six inmates.' Feb 24, 2015 Britain’s first “supersized” Titan prison, which will hold more than 2,100 inmates, is to be run by the public prison service and not a private security company.

As a penologist and criminologist by education, I have been always committed to the mission of offender’s treatment and rehabilitation. After spending a significant amount of time touring and surveying correctional facilities all over the world, I came to the realization that while it is questionable that the world needs more prisons, it is undeniable that what the world needs are better ones to keep pace with the progress in correctional philosophy and practices. Eight years ago, I left academia and joined a planning and architectural firm specializing in justice facilities, discovering the social dimension of architecture and the power of correctional buildings as an alternative solution to moving current penitentiary systems forward (see note 1).

The importance of any correctional facility’s physical plant to the fulfillment of particular objectives has been long recognized. Historically, correctional facilities have been the architectural expression of competing philosophies of incarceration of the time. In the 18th century, when incarceration was instituted as the primary form of punishment in western societies, the prison itself became the means of punishment. As the prevailing punishment method, early purpose-built correctional design reflected punitive patterns reproducing ideals of enforced solitude and intimidation. Prison reform movements at the end of the century and beginning of the 19th century were also followed by reform-oriented design concepts, with the “separate and silent systems” (Pennsylvania and Auburn models respectively), being two of the first architectural manifestations in which the design of the prison building and the availability of space became a factor impacting the reformative potential of the offenders through isolation and labor, therefore including separate cells and larger spatial configurations where prisoners could work together. Although today’s goals of incarceration have little in common with those of centuries ago, with few exceptions, the architecture of incarceration has remained largely standardized throughout the world: large institutions often located in remote rural areas; stark in appearance, with abundant provision of external symbols announcing the building’s function as a place of confinement, and heavy security features asserting absolute control (i.e. tall perimeters topped with razor wire, visible towers and heavy gates). These are characterized inside by bland uniformity in color and textures, and massive cellblocks holding a large number of individuals in gloomy and undersized concrete cells with steel-barred windows and sliding doors, organized along long, narrow corridors. And needless to say, this model of imprisonment has not only constrained the introduction of rehabilitative ideals but has resulted in negative individual, societal and economic impact.

For the last two decades, in the midst of a world-wide prison population growth, the value of correctional architecture as a catalyst for positive outcomes has pushed forward-thinking architects to reassess classical models, rethink prison designs and experiment with innovative spatial concepts embedded with theories from sociology, psychology, and even ecology. These better align the physical plant of correctional facilities with the concept of humane treatment and contemporary priorities of inmate rehabilitation and successful reintegration.

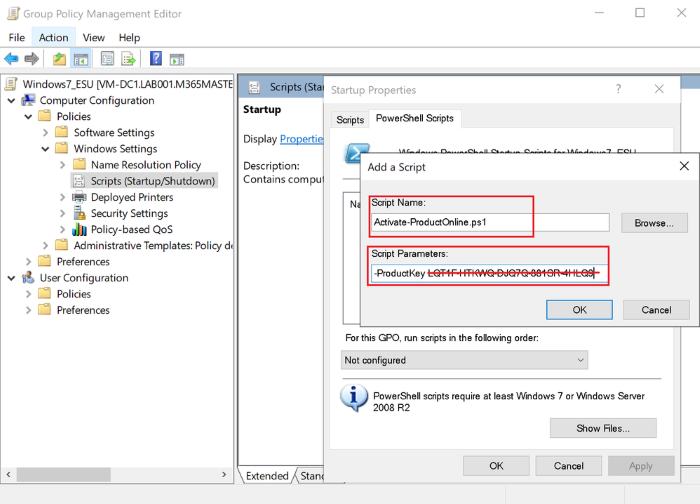

New Generation Jails two key ingredients of new generation approach are architectural design and inmate supervision; began changing in 1970s Release on recognizance (ROR).

The purpose of this blog is to contribute to the discussion about the role that modern facility design can achieve in the topic of correctional reform from the perspective of architects and planners, such as myself. To that end, I reached out to experts in the field, including an environmental psychologist, leading justice planners and several architectural firms internationally known for their sensitive and humane approach to prison design, and asked them to describe in a few paragraphs, the optimal spatial attributes of a prison in which architecture and rehabilitative ideals could operate in harmony (see note 2).

It is not practical or viable to design a “one-size-fits-all” correctional facility, since the type of facility ultimately needed will be influenced by variables such as economic and human resources, political climate, location and the biological, emotional and criminogenic characteristics of those who will reside in the center (e.g., gender, age, risk and needs, and legal status). However, presented below are the features that, drawn from culturally diverse viewpoints, were commonly identified as vital in meeting the basic requirements of inmate rehabilitation (see note 3)…

In order for a correctional building to function as a tool for rehabilitation, the design of a correctional facility should:

Be based on the premise that people are capable of change and improvement, with the built environment conveying the message that incarcerated people are worth something, and that they can be trusted to transform their lives from a criminal past to a more constructive future if provided with the social skills and cognitive tools necessary to succeed.

Be based on “evidence-based practices” and consider the results from scientific research conducted in similar institutional settings like hospitals and long-term healthcare centers, which demonstrate the influence of healthy environments in reducing the frequency and severity of anti-social behaviors and violence, and in mitigating stress and anxiety. More specifically, evidence shows the beneficial mental and social aspects in a treatment-oriented environment of access to natural light and fresh air, connectedness to nature, thermal and acoustic comfort, and variety of outdoor spaces and views to experience the changing of seasons.

Make a “good neighbor”: eliminating the stereotypical intimidating image of prisons and the stigma of incarceration is vital to avoid alienation, and for success in rehabilitation. As a public, social institution, where possible, a correctional facility should be integrated in the community to which the prisoner will be released, and blend with the surrounding area. Although a barrier to the outside world is necessary to maintain security, the aesthetic and environmental aim of the facility should deinstitutionalize the building and integrate it into the broader community by presenting a normalized, modern, citizen-oriented appearance and an appropriate scale.

Two Key Ingredients Incorporated Into New Generation Jails Are In The World

Be right-sized: to carry out a really effective program of rehabilitation, the operational capacity of any correctional facility should never exceed one thousand offenders. The smaller the facility size, the greater the chances for program administrators and facility personnel to get to know many of the inmates personally, their stories, needs, deficits and strengths, and thus better identify effective ways of dealing with them. When held in small enough facilities, inmates may receive more focused attention, programming and individualized treatment. Additionally, evidence-based research shows that large, crowded spaces increase an offender’s sense of isolation and anxiety. Accordingly, to aid in rehabilitation, facilities should be broken down into small units appropriately sized in accordance with security risk and needs. The provision of a variety of housing options (through mixed-custody construction) to satisfy varying degrees of custody as determined by classification requirements, enhances the operation of rehabilitative programs. And to avoid the mixing of inmate groups, each unit should be discrete and self-sufficient, and include both individual as well as a variety of collective spaces where groups of people can congregate to replicate some of the activities they would be engaging in on the outside: cooking, dining, studying, watching television, reading, playing games, and exercising.

Promote safety, security, ease of supervision, and circulation: the demands of security dictate the use of straight-line designs that provide clear sightlines throughout the facility while enhancing way-finding and orientation. At the housing unit level, security through proper supervision is accomplished by organizing the spaces for “direct supervision”, with the officer’s open desk strategically located inside the living area with clear, direct line of sight into the bedrooms (rather than “cells”). Allowing adequate floor space is essential to improve visual openness and make it easier for the officer to see, hear, and supervise inmates. Direct supervision not only aids informal surveillance but also promotes constant, direct interaction and normalized communication between staff and inmates, proactively identifying and addressing potential problems before they escalate. A foundational premise of this approach is that inmates are not confined in their rooms all day, but rather participate in scheduled activities and programming, and are free to move about and use the resources available to them within the housing unit, under less obtrusive security. Allowing inmates a measure of control over their environment results in an environment conducive to change and self-awareness, by encouraging them to manage their own behavior and make responsible choices regarding their participation in daily activities.

Provide a healthy, safe environment: organizations that uplift the morale of those deprived of liberty benefit not only the residents but also staff (who often spend more time in these facilities than the inmates themselves), and the community partners. Spaces that are filled with sunlight, outside views, therapeutic color schemes and normalized materials, encourage inmates’ participation, reduce stress, incidents and assaults and decrease staff absenteeism. The provision of a healthy, safe environment throughout the facility is also essential to encourage community engagement and participation, essential in the success of the rehabilitative mission. Visitors, volunteers and community providers will feel safe if the areas they frequent (eg. public lobby, waiting and visitors’ areas) are welcoming, user-friendly, there is access to daylight, proper ventilation, odors and temperature are controlled and acoustics managed. The same principles apply when designing the administration and staff support spaces, program and service areas, circulation corridors, etc.

Provide a normative (less institutional, more residential-like) and spatially stimulating living environment for occupants: The most effective types of living environments in aiding rehabilitation are those that are domestic in feel and enhance the quality of life. In housing units, a normative, intellectually stimulating environment features abundant sunlight, openness, unobstructed views, landscaping, access to nature, bar-less wood doors and large windows, human scale, movable furniture, normalized materials such as carpet, wood, tempered/shatter-proof glass, commercial grade acoustic lay-in tile low ceiling and acoustic wall panels, functional and home-like furniture, and soft textures and colors: these express calmness, help to ward off monotony and motivate the senses. Additionally, allowing some degree of privacy and personalization are key aspects of the transformation process. Inmates should be entitled to privacy for sleeping, maintenance and personal hygiene, and the safe-keeping of personal items. In turn, personalization of the space should be promoted by, for example, letting inmates personalize their rooms, re-arrange the living area furniture or adjust light fixtures. This promotes a sense of personal dignity and control over the environment, promoting respect for themselves and, in turn, respect for each other.

Be program and services-oriented and provide a variety of spaces: as important as offering inmates a variety of rehabilitation-type programs and services, is the provision of multi-purpose spaces to be used for rehabilitation, such as academic and vocational classrooms, activity and workshop areas, multi-faith space and counseling rooms for both individual and group therapy. Any rehabilitative design should maximize program space, to avoid activities and treatment programs having to compete for the space, therefore compromising inmates’ participation and regular access to programs and services. To encourage positive socialization, movement and the experience of seasonal change, multi-purpose spaces should be spatially organized in a campus-like setting consisting of several stand-alone buildings (rather than a large imposing institution), organized to maximize use of shared resources.

A correctional facility requires a humanizing approach to design that few other kinds of public architecture demand. A new generation of rehabilitation centers should provide spaces that reduce stress, fear and trauma; spaces that stimulate motivation for participation in positive activities that reduce idleness and negative behavior and that, rather than warehouse or isolate inmates, work with them to encourage reformation and reintegration into society as law-abiding citizens. Life inside the secure perimeter of a rehabilitative correctional facility should allow for as much normalcy as possible, providing inmates with a level of responsibility and autonomy that will prepare them for life on the outside, and imposing as few restrictive conditions in spaces, circulation pathways and access to indoor and outdoor spaces as possible. However, for those spatial and environmental considerations and their positive attributes to be of value, they need to go hand- in-hand with positive and constructive inmate management policies, practices and procedures as well as committed, well-trained staff.

Notes

- The broad and generic term of “corrections/correctional facility” includes all types of institutions tasked with housing offenders (eg. jails, prisons, detention centers and juvenile facilities) in this article.

- The author would like to thank the following people and architectural firms for their contribution to this blog: Dr. Richard Wener (Professor of Environmental Psychology at the Polytechnic Institute of New York University), Marjatta Kaijalainen (Finland), Helena Pombares (Angola/UK), Hohensinn Architektur (Austria), Fabre i Torres (Catalonia), PRECOOR SC (Mexico), Parkin Architects Limited (Canada), Jones Studio, Inc. (USA), Jay Farbstein & Associates, Inc. (USA), and CGL/RicciGreene Associates (USA).

- When discussing correctional facilities design, in the interest of brevity, no attempt has been made to differentiate between jails and prisons and juvenile facilities, or institutions of different custody and security levels.

About the author

Dr Marayca López is currently a Senior Corrections analyst and planner for CGL/RicciGreene Associates, a pre-eminent criminal justice planning and design firm based in New York specialising in providing secure and normative environments that promote positive behavioural change and successful re-entry. Having exclusively dedicated her academic and professional careers to the philosophy and practice of prison reform, Marayca is an authority on correctional matters with a deep understanding of correctional facility operations and management. She has participated in correctional projects, both domestically and abroad, contributing to the process of prison reform by providing State and local governments with sustainable, long-lasting criminal justice solutions and right-sized prison infrastructure. Ms. López’s ten years of academic pursuit and practical application in the field of corrections have nurtured and refined her analytical skills, which are critical for criminal justice strategic planning. Her areas of expertise include inmate population analysis, alternatives to incarceration, needs assessments and strategic master planning for criminal justice agencies, and programming of new institutions.

.

About this blog series

To mark our 25th Anniversary and prepare for the Crime Congress in Qatar in April 2015, PRI is running a series of monthly expert guest blogs, addressing interesting current trends and pressing criminal justice challenges in criminal justice and penal reform.

Two Key Ingredients Incorporated Into New Generation Jails Are Called

Blogs will be available here on our website and as podcasts on the 25th of each month from May 2014 to April 2015. Read more about the blog series.